All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a Patient with Liver Cirrhosis: Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

Background:

There are no treatment guidelines for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) for the patients with decompensated cirrhosis, especially for those who have a history of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, gastrointestinal bleeding and gastric fundus ulceration.

Case Presentation:

A 50-year-old woman who had a six-year history of lupus was admitted to our hospital. One month prior, at the Department of Gastroenterology, she was diagnosed with decompensated liver cirrhosis with gastric fundal varicose bleeding, and HBV-related infection. During her visit to the hospital, gastroscopy showed esophageal varices and a large gastric fundus ulcer. Laboratory data indicated the rapid decrease of red blood cells, granulocytes and platelets and the persistent increase of serum globulin levels. According to the patient's medical history and existing laboratory examination, the patient experienced an exacerbation of SLE, which could be life-threatening.-While it remained uncertain whether the liver cirrhosis was caused by SLE or the HBV infection, immediate treatment was necessary. Consequently, she was treated with a low dose of methylprednisolone and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). The treatment resulted in significant clinical improvement. Moreover, there was no indication of HBV reactivation, gastrointestinal bleeding, liver dysfunction or other drug-induced side effects.

Conclusion:

This case indicated that irrespective of the underlying causes of liver cirrhosis, the combination of a low dose of methylprednisolone and MMF is an effective treatment method to inhibit the disease process for patients with SLE and decompensated liver cirrhosis, a large gastric fundus ulcer and HBV infection.

1. INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease that damages multiple systems and has a variety of clinical presentations, such as leukopenia, renal failure, antiphospholipid syndrome and thrombocytopenia. Glucocorticoids (GCs) and immunosuppressive medications are the traditional treatments to induce disease remission in patients with lupus. However, numerous challenges still need to be resolved, such as cirrhosis or gastrointestinal bleeding in SLE patients. Cirrhosis is classified as compensated or decompensated depending on the absence or presence of ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding or jaundice. The prognosis of patients with decompensated cirrhosis is usually very poor, with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 14%–35%. The administration of GCs or immunosuppressive medications to patients with cirrhosis may cause gastrointestinal bleeding, liver dysfunction and other adverse reactions. One controversial question that remains is how to treat the SLE patient with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Here, we report a patient who was diagnosed SLE during the clinical course of decompensated liver cirrhosis with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and a good therapeutic effect was achieved using low-dose methylprednisolone and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).

2. CASE PRESENTATION

A 50-year-old woman was admitted to the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology in our hospital. This patient was diagnosed with SLE when she was 44 years old, but since then, she has not gone to the hospital regularly to receive treatment.

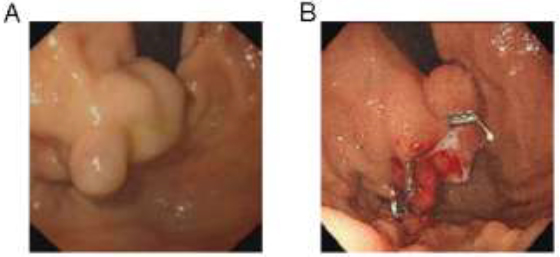

One month prior to her visit to the Department of Gastroenterology, the patient presented with melena and was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis with HBV infection and gastric fundal varicose bleeding. Endoscopy revealed one large isolated fundal gastric varix (Fig. 1A). She underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided coil embolization and absorbable gelatin sponge injection to manage the isolated fundal gastric variceal bleeding (Fig. 1B). The patient was managed concurrently with entecavir. Melena did not reappear after these treatments. Before the patient was discharged from the hospital, a routine examination revealed the following blood parameters: white blood cells (WBC): 3.63×109/L (normal range: 3.5–9.5×109/L), hemoglobin (HB): 94 g/L (normal range: 115.0–150.0 g/L) and platelets (PLT): 114×109/L (normal range: 125.0–350.0×109/L). Because the patient was positive for antinuclear antibody (ANA) and anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), she was informed to follow up with the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology.

| Laboratory Parameters | Result | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cells | 3.18×10^9/L | 3.50-9.50×10^9/L |

| Haemoglobin | 84 g/L | 115.0-150.0g/L |

| Platelets | 54×10^9/L | 125.0-350.0×10^9/L |

| MCV | 91.2 fL | 82.0-100.0 fL |

| APTT | 38.6 s | 29.0-42.0 s |

| PT | 13.9 s | 11.5-14.5 s |

| D-dimer | 2.29 μg/ml | <0.5μg/ml |

| Fibrinogen | 2.47 g/L | 2.00-4.00 g/L |

| AST | 29 U/L | ≤33 U/L |

| ALT | 7 U/L | ≤32 U/L |

| ALP | 119 U/L | 35-105 U/L |

| ϒ-GT | 32 U/L | 6-42 U/L |

| Total protein | 73.5 g/L | 64-83 g/L |

| Albumin | 27.0 g/L | 35-52 g/L |

| Globin | 46.5 g/L | 20-35 g/L |

| Total bilirubin | 13.7 μmol/L | ≤21μmol/L |

| Creatinine | 48μmol/L | 45-84μmol/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 1.16 mmol/L | 3.38 mmol/L |

| Sodium | 140.9 mmol/L | 136-145 mmol/L |

| Potassium | 3.68 mmol/L | 3.5-5.1 mmol/L |

| HBs antigen | 0.09 IU/ml | < 0.05 IU/ml |

| HBs antibody | 6.89 MIU/ml | <10 MIU/ml |

| HBe antibody | 0.14 S/CO | >1.0 OS/CO |

| HBe antigen | 0.35 OS/CO | <1.0 OS/CO |

| HBc antibody | 6.62 OS/CO | <1.0 OS/CO |

| Anti-HCV antibody | 0.12 OS/CO | <1.0 OS/CO |

| HBV-DNA | <1.0×10^2IU/ml | Non-reactive |

| Laboratory Parameters | Result | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| CRP | 3.27 mg/L | 0-5 mg/L |

| ESR | 34 mm/h | 0-20 mm/h |

| IgG | 30.89 g/L | 7-16 g/L |

| IgA | 4.19 g/L | 0.7-4.0 g/L |

| IgM | 0.48 g/L | 0.4-2.3 g/L |

| C3 | 0.60 g/L | 0.8-1.8 g/L |

| C4 | 0.15 g/L | 0.1-0.4 g/L |

| Coombs’ test | (+++) | (-) |

| Anti-β2GP1 antibody | (-) | (-) |

| Anti-phospholipid antibody | (-) | (-) |

| Lupus anticoagulant | (-) | (-) |

| ANA | 1:1000 | <1:100 |

| Anti-dsDNA antibody | 1.97 RU/ml | 0-10 RU/ml |

| Anti-Sm antibody | 41.39 RU/ml | 0-20 RU/ml |

| Anti Ro-52 antibody | >400.00 RU/ml | 0-20 RU/ml |

| Anti-SSA antibody | >400.00 RU/ml | 0-20 RU/ml |

| Anti-SSB antibody | 38.87 RU/ml | 0-20 RU/ml |

| Anti-rRNP antibody | <2 RU/ml | 0-20 RU/ml |

| Anti u1-nRNP antibody | >400.00 RU/ml | RU/ml |

| Anti-mitochondrial M2 antibody | (-) | (-) |

| Anti-smooth muscle antibody | (-) | (-) |

| anti-LKM1 antibody | (-) | (-) |

| Anti-GP210 antibody | (-) | (-) |

| Anti-SP100 antibody | (-) | (-) |

| PR3-ANCA | <0.2AI | <1.0AI |

| MPO-ANCA | <0.2AI | <1.0AI |

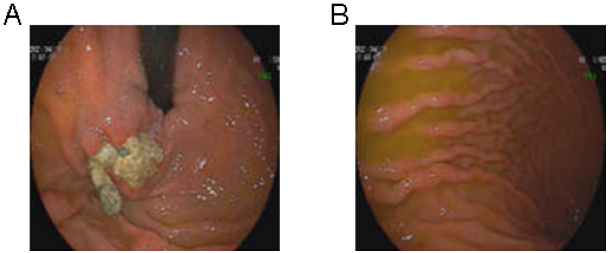

Upon the patient’s admission to the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, there was no obvious rash, ulcers, swelling or tenderness of the joints. The laboratory data illustrated in Table 1 showed pancytopenia (WBC 3.18×109/L, HB 84 g/L and PLT 54×109/L), which was worse than that of 1 month prior. The serum levels of globulin and albumin were 46.5 g/L and 27 g/L, respectively. Bone marrow aspiration, bone marrow trephine biopsies and electrophoresis of serum proteins did not show any significant abnormalities, ruling out hematological malignancies or hematopoietic dysfunction. Fecal occult blood testing yielded normal results, and urinalysis did not show any signs of proteinuria or occult blood. However, the serum samples showed high levels of ANA, anti-Smith (anti-Sm), anti-U1-ribonucleoprotein (anti-U1-RNP), anti-Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A (anti-SSA), anti-Ro52 and anti-Sjögren’s syndrome B (anti-SSB) antibodies. Serum level of complement 3 (C3) was decreased to 0.6 g/L, whereas the level of IgG was increased to 30.89 g/L. The result of the Coombs test was strong positive (+++). Screening for anti-smooth muscle antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody and anti-liver-kidney microsomal type 1 (LKM1) antibody determined that the serum sample was negative for these antibodies; the autoimmune hepatitis panel was also negative (Table 2). Repeated gastroscopy revealed the presence of gastro-esophageal varices with a large gastric fundus ulcer, which had developed as a result of the earlier coil embolization and absorbable gelatin sponge injection (Fig. 2). Abdominal echography revealed liver cirrhosis and splenomegaly, but no ascites, cholecystitis was observed. The gastroenterologist informed us that splenomegaly could not explain the pancytopenia, and using prednisolone posed a high risk of bleeding due to the gastric fundus ulcer.

| Laboratory Parameters | Result | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cells | 4.47×10^9/L | 3.50-9.50×10^9/L |

| Haemoglobin | 92 g/L | 115.0-150.0g/L |

| Platelets | 111×10^9/L | 125.0-350.0×10^9/L |

| MCV | 77.3 fL | 82.0-100.0 fL |

| ESR | 28 mm/h | 0-20 mm/h |

| AST | 15 U/L | ≤33 U/L |

| ALT | 30 U/L | ≤32 U/L |

| ALP | 89 U/L | 35-105 U/L |

| ϒ-GT | 39 U/L | 6-42 U/L |

| Total protein | 76.6 g/L | 64-83 g/L |

| Albumin | 35.3 g/L | 35-52 g/L |

| Globin | 41.3 g/L | 20-35 g/L |

| Total bilirubin | 9.8 μmol/L | ≤21μmol/L |

| Creatinine | 55μmol/L | 45-84μmol/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 3.17 mmol/L | 3.38 mmol/L |

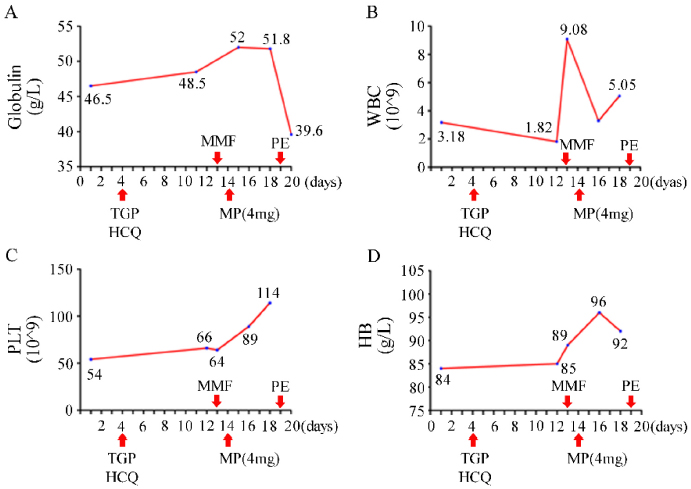

Treatment with total glycosides of paeony (TGP) and hydroxychloroquine sulfate (HCQ) was started on day 4 of hospitalization. However, despite the treatment, improvements in the patient's leukopenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia were not observed. The WBC dropped to 1.82×109/L two weeks after admission. The serum level of globulin continued to increase unabatedly. The patient refused the therapy of gamma globulin and biologic agents for personal reasons, and oral methylprednisolone tablets at a daily dose of 4 mg and MMF 0.25 g twice daily were added. With the patient's permission, plasma exchange (PE) was performed once. Pancytopenia improved rapidly and serum globulin did not continue to increase significantly (Fig. 3). Upon the patient's discharge from the hospital, instructions were provided to adjust the dosage of MMF to 0.5 g in the morning and 0.25 g in the evening, while continuing the intake of methylprednisolone, HCQ, and entecavir as prescribed previously. At the outpatient visit three months later, the patient’s WBC increased to normal and serum globulin returned to 41. 3g/L (Table 3). No side effects of the drugs were evident.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on clinical presentation and laboratory tests, this patient was diagnosed with SLE according to European League against Rheumatic Diseases and American College of Rheumatology criteria in 2019. Hyperglobulinemia and pancytopenia were correlated with disease activity in SLE. She had a history of liver cirrhosis with gastrointestinal bleeding and HBV infection. After admission, the gastroscopy showed oesophageal varices with a large gastric fundus ulcer, which resulted from Child-Pugh B liver cirrhosis. Although the SLE Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score for this patient was 4, the laboratory data indicated an exacerbation of SLE, necessitating urgent treatment. However, it was necessary to choose the type and dosage of medicine carefully because of the risk of drug side effects in this patient.

The treatment of most patients with severe lupus necessitates GCs in combination with immunosuppressive drugs to induce disease remission. However, GC-mediated effects prevent wound repair and induce peptic ulcers (upper gastrointestinal ulcers) in a dose-dependent manner. A retrospective analysis of the incidence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients treated with GCs found that patients with a history of upper gastrointestinal bleeding were more likely to have recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding. One study investigating the dose and duration of prednisone intake by patients with rheumatoid arthritis determined that the frequency of adverse events increased with prednisone dosage, and there was a threshold pattern at 5–7.5 mg/day.

It has been long recognized that immunosuppressive therapy in patients with rheumatic diseases could result in the reactivation of HBV, which is characterized by abnormal liver function, increased levels of serum HBV DNA and hepatic failure. Corticosteroids have been shown to be an independent and additive risk factor for HBV reactivation. The risk was closely related to the dosage and duration of prednisone. The authors identified that a daily dose of prednisolone greater than 5 mg could be a risk factor for HBV reactivation. One prospective cohort study of idiopathic patients with nephrotic syndrome positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs Ag) with ‘undetectable’ HBV DNA (<1.000 copies/mL) was reported. Compared with the standard prednisone regimen, the combination therapy of MMF and a reduced prednisone dose resulted in better remission rates in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. The combination-therapy group had lower rates of HBV reactivation. Interestingly, other studies indicated that MMF inhibits the replication of HBV and enhances the anti-HBV effect of entecavir.

Because, to date, there are no guidelines for the treatment of SLE with decompensated cirrhosis, 40% of HBsAg-positive patients who were treated with immunotherapy experience hepatitis flare. Drug-induced liver injury is regarded as the main cause of liver dysfunction in patients with SLE. The disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) that were most frequently associated with hepatotoxicity were azathioprine and methotrexate. Cyclophosphamide and leflunomide were less frequently associated with hepatotoxicity. The DMARDs, that induced hepatotoxicity rarely, were cyclosporine, hydroxychloroquine, MMF and tacrolimus. MMF, tacrolimus (FK506), and cyclophosphamide were not directly related to fibrosis. There was no optimal choice for the treatment of SLE with cirrhosis among these three drugs.

The cause of the patient’s liver cirrhosis was not clear. The present patient had four years of SLE history, and the liver cirrhosis may have been caused by lupus hepatitis (LH) or HBV-related hepatitis. Some experts recognized LH as a subclinical liver dysfunction resulting from SLE. That study found that patients with LH and cirrhosis had a significantly higher rate of thrombocytopenia and leukopenia and a higher level of IgG [13]. The most common feature of LH was mild (< 5×ULN, the upper limit of normal range) to moderate (5–10×ULN) liver enzyme elevation. Zheng et al. reported that there was a 9.3% incidence of LH in 504 SLE patients that were evaluated. It was recommended that LH should be diagnosed by initially ruling out viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease and other secondary causes of liver involvement. The liver pathology observed in LH presents as various and nonspecific histological changes, such as non-alcoholic liver steatosis, lobular inflammation, interface hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, focal necrosis and nodular regenerative hyperplasia [16, 20, 21]. Complement deposition and vasculitis lead to liver cell necrosis and regeneration, indicating the development of liver cirrhosis [22-25]. However, this complication is very rare, and there are no clear recommendations to perform a liver biopsy. In addition to the biochemical abnormalities in liver function, autoantibodies to ribosomal P proteins (anti-rRNP antibodies) are highly specific markers for LH. Several reports have even suggested that LH was caused by these autoantibodies. One international multicenter study indicated that the sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic efficiency of anti-rRNP antibodies were 21.3%, 99.3% and 65.3%, respectively. To date, there is no standardized treatment for LH, although GCs are considered an effective treatment. LH is frequently associated with SLE flares or disease activity, which could return to normal after corticosteroid treatment [17, 26, 30, 31]. One case discussed an LH patient who was refractory not only to corticosteroids but also to immunosuppressants like azathioprine, cyclophos-phamide and tacrolimus [32]. However, MMF rapidly controlled the disease activity, despite a reduction in the dose of methylprednisolone.

CONCLUSION

In summary, we report a patient with a history of decompensated liver cirrhosis, HBV infection and gastric fundal varicose bleeding. Following EUS-guided coil embolization and absorbable gelatin sponge injection, gastroscopy revealed the presence of esophageal varices and a large gastric fundus ulcer during follow-up. The patient, who had a long course of lupus, deteriorated rapidly and was in critical condition. To choose the most appropriate drugs, we had to balance the potential benefits with the possible risks. Finally, the combination of a low dosage of methyl- prednisolone and MMF proved to be an effective treatment without obvious medical side effects in this present case. Nevertheless, further clinical trials including larger numbers of patients are needed to assess the efficiency and safety of this approach.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SLE | = Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| GC | = Glucocorticoids |

| HBV | = Hepatitis B virus |

| MMF | = Methylprednisolone and mycophenolate mofetil |

| TGP | = Total glycosides of paeony |

| HCQ | = Hydroxychloroquine sulfate |

| PE | = Plasma exchange |

| DMARDs | = Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs |

| AST | = Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALT | = Alanine aminotransferase |

| ANA | = Antinuclear antibody |

| EUS | = Endoscopic ultrasound |

| LKM1 | = Liver-kidney microsomal type 1 |

| HB | = Haemoglobin |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

CARE guidelines were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (Y.H) on reasonable request.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Science Fund of China (81703058).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.